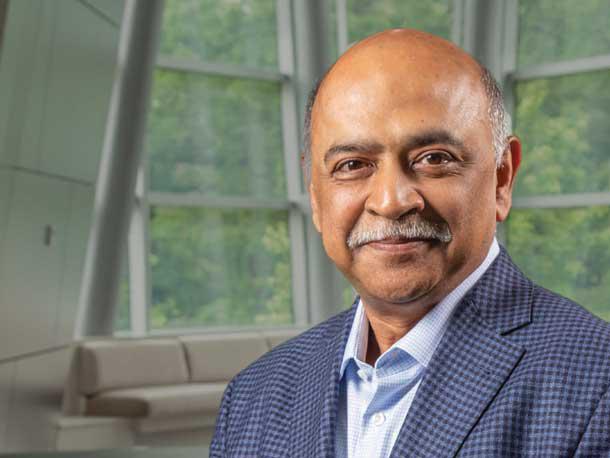

IBM CEO Arvind Krishna’s ‘Deeply, Deeply Passionate’ Plan To Make IBM-Red Hat No. 1 In Hybrid Cloud, AI

IBM Chairman and CEO Arvind Krishna is transforming the company into a hybrid cloud and AI powerhouse focused on a $1 trillion market opportunity with a plan to double its revenue with partners over the next three to five years.

When EY Global Chairman and CEO Carmine Di Sibio broke bread with IBM Chairman and CEO Arvind Krishna last July at a luncheon meeting, the two companies were more “frenemies” than partners. “

It was not a great relationship,” said Di Sibio. “We were more competing than we were friends.” That all changed when Krishna laid out IBM’s new partner ecosystem charge that was taking hold in the wake of IBM’s blockbuster acquisition of Red Hat.

“The message I got at lunch was IBM was changing, [going through a] transformation, and the Red Hat acquisition was a big piece of this,” he said.

[RELATED: IBM CEO Arvind Krishna: 10 Boldest Statements From CRN’s Exclusive Interview]

Di Sibio was impressed and as a result has made a big bet on Krishna and IBM. Now, the New York-based $37.2 billion global consulting powerhouse is aiming to drive $1 billion in revenue from the IBM partnership over the next few years. Di Sibio said he has been heartened by the speed at which Krishna is driving the transformation at IBM. “IBM notoriously has been, I’ll say, moving slower,” he said. “I do think they have changed, and they are changing. I have confidence they are going to move fast.”

The Red Hat deal, in fact, has changed the “culture” at IBM and the ecosystem strategy for the better, said Di Sibio. “Their change in strategy really enabled us to have a different type of relationship,” he said.

Key to building a strong partnership has been Krishna’s technology savvy as a leader, his partnership commitment and the trust that has developed between the two executives, said Di Sibio. “Arvind is pretty technical,” he said. “I think he is the right choice for where their strategy is going as they move forward.”

Since that lunch meeting, EY and IBM have combined on a joint go-to-market plan centered on the IBM Financial Services Cloud, combining EY’s financial consulting muscle with IBM’s cloud prowess. The two companies also launched just two months ago EY Diligence Edge, an AI-enabled M&A due diligence platform hosted on IBM Cloud and supported by IBM Watson Discovery.

EY had opportunities to use different cloud providers for EY Diligence Edge but chose IBM because of its hybrid cloud strategy and Watson AI technology as a “differentiator,” said Di Sibio. He said the IBM technology is helping win M&A customers for EY. “I think Arvind is bringing IBM back to being an innovative technology company based on hybrid cloud,” he said.

The EY partnership is just one piece of Krishna’s bold bet on partners with the company’s biggest go-to-market change in three decades as part of his “maniacal focus” to make IBM the No. 1 provider of hybrid cloud and AI.

“I think it’s the biggest change we have made in our go-to-market [model] in my living memory,” said Krishna, who started his career at IBM in 1990 as a researcher at its Thomas J. Watson Research Center. “If you think about how we pay our people and how we have got clarity on the partners, it is the single biggest change in 30 years on the go-to-market. It is massive.”

For Krishna—the architect of IBM’s $34 billion acquisition of Red Hat 19 months ago—a new simplified sales structure with a renewed emphasis on partners that launched earlier this year is the next logical step in his reinvention of IBM as a cloud superpower.

It is a transformation that Krishna—who is clearly relishing the faster pace of change he has driven since taking over the CEO post on April 6—is “deeply, deeply passionate about.” The new organizational structure is aimed at unleashing a full-fledged IBM partner ecosystem to win the architectural battle in the cloud with Red Hat OpenShift as the “default choice” for hybrid cloud and AI. That means eliminating IBM direct sales competition with partners through a new simplified sales structure that focuses IBM’s global direct sales force exclusively on the biggest accounts and leaves the rest of the market—literally 100,000 accounts that previously were manned by IBM sales reps— to IBM ecosystem partners. That new account engagement model—backed up by a $1 billion IBM investment to elevate the role of partners—puts solution providers on the front lines driving cloud consumption with Red Hat OpenShift, IBM Cloud Paks and IBM public cloud.

Make no mistake about it, said Krishna, the new sales structure, which has reduced the number of customer groups in IBM from 50 to just two, has resulted in a sales commission model that is “highly favorable” to the channel. No longer will IBM global direct sales reps focused on the biggest accounts be able to move into the midmarket and get paid a commission on those deals, said Krishna. “You cannot get paid [as an IBM global direct sales rep] for what is today a midmarket client,” he said of the new IBM internal compensation model. “Suddenly that is a big plus for the partner.” Beyond that, there is going to be a large force of IBM brand specialists who are going to be paid for working hand in hand with IBM ecosystem partners to drive sales growth in the partner-led segment, said Krishna.

The new go-to-market model marks the first time since taking the helm of Armonk, N.Y.-based IBM that Krishna has put the full weight of IBM’s ecosystem partners behind the hybrid cloud and AI sales offensive. Krishna, in fact, sees the opportunity for IBM to drive a partner renaissance that harkens back to the astronomical sales growth many partners experienced first with IBM’s mainframe platform and then with its deep middleware software portfolio at the turn of the century with offerings like WebSphere, IBM DB2 and Informix.

“We made tens of billions and they made hundreds of millions in aggregate over the decades,” said Krishna, reflecting on IBM’s mainframe and middleware software success teaming with partners in the past. “I would like to see our hybrid cloud platform be as big or bigger than any of those. If you take the mainframe, by the way, over its 50 years, that is hundreds of billions [of dollars]. You could debate whether it’s trillions [of dollars]. I would like to see our hybrid cloud platform be that big and that sustainable. That means sustainable for decades, not just for a few years. That is my vision for us and our partners together.”

The vision, Krishna said, is for IBM to double its revenue with partners over the next three to five years in what he says is a $1 trillion hybrid cloud market. “I want our partners to be the best at establishing a hybrid architecture at our clients and establishing an AI footprint at our clients,” he said.

A Win-Win-Win

Krishna said his philosophy on the partner ecosystem value proposition is simple: “Anything that succeeds in this world has to be a win-win-win. It has to be good for us, it has to be good for the partner, and it has to be good for the client,” he said.

Under the new go-to-market model, IBM will go direct to the 500 largest customers seeking an “integrated” set of solutions from IBM, said Krishna.

“Segment one we really want to be direct for products,” he said.

Even in that direct sales large account segment there is still a “massive market” for the channel given that there is on average $5 for build and service on every $1 of products sold, said Krishna.

“There is a certain set of clients where we will largely go direct for the product sale,” he said. “There is a big role for partners around providing, whether you use the word ‘build’ or ‘service,’ because not every customer has got the capacity or even the desire to do it all themselves.”

In the next segment of several thousand accounts, Krishna said, IBM will “go somewhat directly, but there is more opportunity for partners, including in the resale of products.”

Beyond those next several thousand accounts, the go-to-market is completely through partners, said Krishna. “I really want to depend only on partners [there],” he said.

Krishna is determined to build a robust ecosystem of partners working hand in hand with IBM to educate customers on why the “best architecture for clients” is an IBM Linux Kubernetes container platform on-premises and in the public cloud. “If we can get that through [to the partners and the market]—which is a massive advantage, we believe, for our clients and our partners— then there is a lot of money to be made because we are going through this tectonic shift,” he said.

That tectonic shift, said Krishna, is all about driving the next big paradigm shift in technology. He saw it take place firsthand with the mainframe-based model and then the client/server model and now with a new application modernization revolution through the Red Hat OpenShift hybrid cloud architecture. This new era will be marked by a pronounced shift from infrastructure to services, said Krishna. “Our partners should be putting their money into build and service as opposed to just infrastructure,” he said.

The Reinvention Of IBM

For Krishna, the rearchitecting of IBM’s go-to-market model is the next major step in his reinvention of IBM into a fast-moving, hybrid cloud and AI superpower. That transformation began more than two years ago with Krishna, who was then senior vice president of cloud and cognitive software, working feverishly to close IBM’s acquisition of Red Hat, Raleigh, N.C.

The Red Hat deal—IBM’s largest deal ever and one of the largest deals in tech history—gave IBM the technology to become a force to be reckoned with in cloud with Linux, containers and Red Hat OpenShift. It also gave IBM a new architectural platform, put in place by Krishna in his previous role, to break down the longstanding barriers between public and private cloud with a “write-once, run-anywhere” open hybrid cloud platform architecture.

Krishna’s next audacious move: a plan, set in motion four months ago, to accelerate the hybrid cloud transformation by splitting IBM in two by creating a publicly held spin-off of its behemoth Global Technology Services’ (GTS) managed infrastructure services unit. That managed services infrastructure spin-off—a move expected to be completed by the end of this year—creates a $19 billion business with 4,600 clients that is currently dubbed “NewCo.” It also sets the stage for deeper hybrid cloud partnerships with the channel and a robust Red Hat OpenShift ecosystem.

Now Krishna is putting all the pieces in place to ensure the hybrid cloud partner ecosystem model is a top priority in 2021. That includes giving IBM Senior Vice President Bob Lord, the onetime former COO of dot-com solution provider darling Razorfish, the task of driving an expanded partner ecosystem to support the IBM hybrid cloud and AI model.

Krishna’s call to action, said Lord, is for him to “step up” and “really go hard” on building out the Red Hat OpenShift partner ecosystem. That means getting global systems integrators, IBM’s traditional VARs and VADs, ISVs and finally IBM’s Global Business Services group all focused squarely on driving the Red Hat OpenShift cloud model.

The driving force behind the new ecosystem build-out, said Lord, is Krishna’s crystal-clear software vision. “His software vision is so dead-on,” he said. “I have a platform to go talk to each of those four sectors in a way that I could not have done before. This is our hybrid cloud architecture and platform and AI solutions, and this is how you can bring it to market: first, how you bring value to your clients but also how you make money and how you get value out of this whole equation. I think sometimes we may have missed that piece.”

Lord said he is moving fast to build out the Red Hat OpenShift ecosystem, drawing up billion-dollar business plans with top global systems integrators and accelerating midmarket relationships with VARs and VADs, but the “real opportunity,” he said is driving ISVs to embed OpenShift into their software offerings.

“We have to make it easier for ISVs to on-board with us,” he said. “We’ve got to give them some economic models that make sense to them. The great news with OpenShift is it gives a software vendor flexibility to run on multiple environments. So there is a real business need of why they would want to get on Red Hat OpenShift for their business model.”

The epochal moment for the new partner ecosystem model came with Krishna’s acquisition of Red Hat, said Lord. “The watershed moment for me was the acquisition of Red Hat because it fundamentally pivoted the company,” said Lord. “The second watershed moment, though, is having Arvind be very clear about what the software strategy is, having us develop this platform, the mandate around OpenShift so that we can activate the ecosystem at scale.”

Lord said the new go-to-market model means IBM is no longer competing with its partner ecosystem in the Red Hat OpenShift architectural cloud battle. “We’re supporting the ecosystem with OpenShift,” said Lord. “We’re not competing against the ecosystem. That is the subtlety in 2021. ... It’s a big change.”

IBM has started the ISV build-out with targeted cloud ecosystems such as the IBM Financial Services cloud, where it has 75 ISVs that have now committed to build on top of it.

At Razorfish, Lord was driving big sales growth by leveraging IBM’s WebSphere e-commerce server. At that time WebSphere was driving 30 percent to 40 percent annual sales growth, said Lord. Now, he said, he is working with partners to drive similar services growth at IBM for partners. “I’m now on the other side of it here, which is kind of exciting,” he said.

IBM is taking the same recipe for success that propelled dramatic growth for IBM WebSphere and using it to drive Red Hat OpenShift into the marketplace, said Lord. “We’re taking that same [WebSphere] formula now, certifying people on OpenShift and [educating them on] what does Red Hat do, and we are going out to the ecosystem,” he said.

Lord said he is focusing 50 percent of his time in the first six months of the year building out billion-dollar business plans with the top 10 global systems integrators. The remaining 50 percent of his time, he said, will be working on scaling the other channel ecosystem initiatives.

The GSI effort represents a major commitment of investment and resources from both IBM and the partners, said Lord. Among the major GSI relationships are HCL Technologies, Infosys and Wipro, said Lord. The emphasis is on creating a unique value for each of the systems integrators, said Lord. “My job is to make sure they get the resources to actually help build those business plans, quite honestly, for them to make money,” he said. “Because I know if they make money, then I will make money. I have to think first about their value proposition and how they are going to make money, and then ultimately I make money right after it.”

Besides the global systems integrators charge, Lord is promising an all-out partnering effort in the midmarket with ecosystem leaders in all of IBM’s geographies leading the charge. “There is a lot of energy around that midmarket,” he said.

Those midmarket partnerships will be driven in the individual markets, where new ecosystem leaders have been named with responsibility for building and driving those relationships in concert with an IBM technology leader who owns the hardware-software business, said Lord. “They are working together to drive the adoption of the software and hardware,” he said. “The segmentation that has been rolled out eliminates a lot of the conflict in the market.”

The ecosystem leaders are charged with recruiting new partners and even established IBM midmarket partners to drive the new hybrid cloud and AI architectural model. The bottom line is partners that adopt the new cloud consumption model with Red Hat OpenShift, IBM Cloud Paks and IBM public cloud will see more “energy” from IBM going forward, said Lord.

Those partners sticking with pure reselling and not moving to a consumption model will find themselves getting “less energy” from the IBM ecosystem effort, said Lord.

“For those partners that actually help to drive the software consumption they are going to get the energy, the recruitment, the resources and the trainings that they need in market,” he said. “So it is going to be less of a peanut butter spread and much more of a targeted spread in the market. So if you’re a midtier partner and you have an expertise in insurance infrastructure and modernization, we are going to want to work with you because we are going to want you to take our hybrid cloud platform in with OpenShift into that market for us and go and provide the service. Also if you are a partner that has a very big sales force we are going to want to make sure we get in bed with you because we want more sellers out on the street, selling and talking about this new infrastructure and where this is going,” he said.

IBM Is Putting Its Money Where Its Mouth Is

Rich Hume, CEO of Tech Data, the distribution behemoth that is mounting its own $750 million next-generation digital transformation offensive focused on helping solution providers drive cloud, AI/data analytics and the Internet of Things, said Krishna’s go-to-market changes translate into big opportunities for partners driving hybrid cloud and AI solutions.

“It is a very bold step, and it clearly will benefit the partners,” said Hume of the new IBM ecosystem emphasis and the simplified go-to-market model. “Under Arvind’s leadership, I certainly see them putting their money where their mouth is and investing in the channel to help go drive the change to their new offerings.”

In fact, Hume said, in “traditional IBM style,” the company has put together a lucrative incentive stack ensuring that partners who engage and sell IBM offerings will make “good money.”

Hume, who spent 30 years at IBM before joining Clearwater, Fla.-based Tech Data in 2016, applauded the cultural transformation at IBM under Krishna. “Arvind is absolutely the right person to lead IBM as the world goes through this major [hybrid cloud] technology transition,” he said. “I applaud the work they have done to their go-to-market and engagement model. It is as simple as IBM has ever made it. They [now] have two major segments, and the IBM coverage will be concentrated on the first tier of customers. The second tier of customers will have the right set of IBM resources to help drive the business, but there will be a shift toward the channel and a higher reliance on the channel ecosystem to drive that business.”

The dramatic investment in ISVs will also benefit partners, said Hume. “As they invest in bringing more ISVs, it just means more offerings and more capabilities for the channel to go sell,” he said, noting it was the heavy investment in applications that drove IBM AS/400 sales into the stratosphere in the 1990s. “What made that platform and what allowed us to grow the channel ecosystem exponentially was the very significant ISV presence,” he said.

By simplifying the go-to-market model, IBM has unleashed more opportunity for partners in the hybrid cloud/AI market, said Tech Data President of the Americas John O’Shea, a former president of managed services superstar Vology. “The pie for the partner ecosystem just got bigger,” he said. “The pie just grew incrementally. Now it is about all of us jumping in, activating that and taking advantage of that opportunity.”

IBM—under Krishna’s leadership—has put in place the laser focus and sales alignment with the proper compensation model to drive growth in the Red Hat OpenShift hybrid cloud/AI platform, said O’Shea. IBM has “gone all in” on the hybrid cloud transformation that is taking hold in corporate America, said O’Shea.

“This is huge,” he said. “Think about the shift that Arvind is making with IBM. He is betting the house that is what is required. You can’t be halfway in. The difference is IBM is not putting their toe in the water here. They are all in.”

The IBM go-to-market changes are driving new opportunities for both IBM legacy partners and new partners looking to take advantage of the hybrid cloud-AI revolution with the Kubernetes Red Hat OpenShift stack, said O’Shea. “I actually believe you are going to see IBM expand their partner base as a result of this,” he said, noting the hybrid cloud pie provides “plenty of room” for both legacy and new IBM partners to grow the business.

Winning The ‘Architecture Battle And Not The Destination Battle’

C Vijayakumar, president and CEO of global systems integrator HCL Technologies, which just passed the $10 billion mark in 2020, up from $6 billion in 2016, said Krishna’s technology smarts are leading to more opportunities for IBM partners.

“Arvind really wants to win the architecture battle and not the destination battle,” he said. “Customers can choose the [cloud] destination of their choice, but IBM wants to win the architecture, which is around open source, hybrid cloud, OpenShift and Red Hat. It is a very customer-centric strategy, and the speed at which Arvind is executing is also very admirable.”

Noida, India-based HCL, for its part, is responding with a plan to increase the number of IBM-Red Hat engineers fourfold from 1,000 to 4,000 over the next two years as it aims to dramatically scale up the IBM practice.

Many customers simply do not have a full appreciation of the power of the middleware software portfolio that Krishna has pulled together at IBM under the Red Hat open-source banner, Vijayakumar said. “People have to understand the importance that middleware plays in this whole architecture conversation,” he said.

Not often recognized is that IBM has what may well be the largest installed base of middleware software—much of that software acquired by HCL for $1.8 billion in 2018. Modernizing that legacy middleware installed base with IBM-Red Hat is a “huge opportunity” to bring hybrid cloud and AI to customers with Linux, Red Hat OpenShift and Ansible, said Vijayakumar.

Backing up the IBM-Red Hat bet with a simplified go-to-market model is also opening up more opportunities for partners, said Vijayakumar. “I strongly believe this new approach will further simplify and make it easy and allow us to scale the whole IBM practice significantly,” he said.

The new client engagement model provides a much “clearer” path for partners like HCL to go to market with IBM, said Vijayakumar. It also increases the “addressable market” for ecosystem partners. “It gives us an opportunity to work with a lot of IBM clients,” he said.

That is a “very, very big” breakthrough for IBM and its partners, he said. IBM has consciously made a choice to focus its direct sales teams on a subset of clients and trusting ecosystem partners to work with other clients, said Vijayakumar. “I think it’s a very smart strategy,” he said.

The way Vijayakumar sees the new strategy is IBM will focus on the biggest customers looking for an “overall integrated proposition” from IBM, play a role with a set of customers looking for “niche” IBM capabilities, but leave the rest of the market to ecosystem partners like HCL.

Krishna’s passion for partners to succeed is “very, very visible” in the actions he has taken to improve the IBM partner proposition, said Vijayakumar. “Arvind cuts to the chase very quickly,” he said. “He comes to the point. It is very easy to work with him. He is extremely client-centric.”

The Education Of CEO

Krishna—who grew up in India and came to the U.S. to earn a Ph.D. in electrical engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign—said he was “blessed to have a lot of help and a lot of mentors” in his journey from a highly respected engineer at IBM to the CEO job. It’s a journey that took him from a young man working on technology breakthroughs to a seasoned builder of businesses, moving beyond technology invention to driving market adoption.

When Krishna first started at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center in 1990 he understood just how transformational the internet would be for the world, even though it was five years before Netscape would introduce the first internet browser. “For those of us in engineering graduate school in this country, we knew the internet was there,” he said.

Krishna decided to focus on wireless networking with a team of lab employees. The IBM team put together research prototypes for a Wi-Finetwork with the idea of supporting billions of endpoints. “We were talking to the product side of the house and some of them got excited and they said, ‘There is a market for 1,000 of these,’” recalled Krishna. “I looked at them and I said, ‘There is a market for a billion of these, not for 1,000 of these.’”

The challenge, of course, was getting the product team at IBM to realize just how big the market opportunity was for Wi-Fi. Krishna saw it as a matter of building a custom ASIC to dramatically drive down the cost of Wi-Fifrom thousands of dollars to just several hundred dollars. “People just couldn’t see the market [would] be that big,” he said. That’s when Krishna realized he had to play a role in not just the technology creation side of the business but as the head of a business within IBM.

That move from pure technologist to technology entrepreneur of sorts led Krishna to realize that to be successful a company needs to have a robust go-to-market model. “My first big learning was I have got to straddle both sides, [the technology and the business aspects of IBM],” he said. “The moment you begin to straddle both sides it actually goes straight to this conversation. So even if you build the best technology, how do you get it to market? Who is going to sell it? Who is going to service it? Who can explain the value to the client? Who can help them deploy it? If you don’t get through all those questions, it is a science lab experiment at the end of the day.”

At the same time he was gaining a deep understanding of go-tomarket dynamics, he was also developing a strong sense of driving customer value. That led him to look closely at making sure any technology decision was based on customer feedback. “At the end of the day if the client doesn’t see value, they are going to stop paying you for it,” he said. “That was a big learning.”

Another big career moment for Krishna came when he began working with former IBM software executive Robert LeBlanc in the 2001 time frame. At that point, LeBlanc asked Krishna to help build a security software business around IBM’s Tivoli systems management offering. “He took a chance [on me],” said Krishna. “He took this guy who was an engineering guy, who knew how to build product, and said, ‘Come help me build a security business.’”

LeBlanc gave Krishna carte blanche on whether to build or buy IBM’s security portfolio. “That three years was an incredible learning experience across [all] those different dimensions … including M&A, including big divestments, including how do you take care of customers when you do both those things,” he said.

After building the security business, Krishna learned the channel inside and out when he took command of the Informix database business in the mid2000s. “That’s when I really got to understand the channel really, really well because Informix was almost 90 percent a channel business—mostly resellers,” he said. “But every one of them had a secret sauce. Some could solve a problem in their sleep. You would call up these guys and they could tell you ‘Just change this knob and you are fixed.’ Others would be building massive applications on top of Informix. But the application was what the clients wanted, not Informix.”

For Krishna, the Informix experience gave him a profound appreciation for how partners of all kinds team with a company like IBM to build a successful business. “Their expertise and [the value they bring] to the client is what helps us make money,” he said. “You actually have to cover the gamut [of the partner ecosystem] to succeed as a business,” he said.

Execution Key To Channel Ecosystem Renaissance

IBM has already begun communicating about the new go-to-market model, pledging to bring more client opportunities, technical resources and support to partners.

In a memo titled “Elevating IBM’s Partner Ecosystem To Deliver Open Hybrid Cloud and AI At Scale,” IBM has promised “more investments in client coverage where IBM sellers are focused on jointly selling with partners.” That includes additional demand generation funding and digital campaign capabilities, and an expanded cloud engagement fund for supporting partners helping customers modernize applications. “We’re bringing you more investment, support and opportunities than ever before, and striving to do that in a simplified way,” said IBM in the memo to partners.

Partners said IBM’s new mantra for partners—“Value to the clients + Value to partners = Value to IBM”—represents a dramatic new recognition of the role partners play. What’s more, they said, the clarity in the partner model feels like the middleware software sales offensive that was so successful in the ’90s.

IBM partners said they are excited by the potential for the new partner ecosystem model, even though IBM still hasn’t worked out all the details. Specifically, partners are champing at the bit to tackle those thousands of new account opportunities that were at one time covered by IBM client reps. Key to the client engagement model is specific account sales planning. Partners are also anxious to get more details on how to work with the multiple IBM technology brand specialists to accelerate sales growth.

John McCarthy, president and CEO of Tallahassee, Fla.-based Mainline Information Systems, who over the past 12 years has built the onetime primarily IBM shop into a $1 billion-plus cloud best-of-breed solution powerhouse, said he sees IBM’s new engagement model as a big change that could provide a significant revenue uplift for partners.

“It’s a great strategy and a great plan,” said McCarthy. “We’ve been with IBM for 33 years, and there is a lot of hope and expectation around this. We’re still awaiting the details and looking forward to seeing over time whether it develops like we hope it does. It’s no longer about words. Now it is all about execution.”

A big positive sign in the rollout of the new engagement model is the direct involvement of IBM Americas General Manager Ayman Antoun, said McCarthy. “He is one of the architects behind this and is really stepping up to make it happen,” he said. “That’s a big plus for IBM. When Ayman gets involved, things get done.”

Mainline has won numerous awards for its solutions strategy— including Dell Technologies’ 2020 Growth Partner of the Year alongside its 2020 IBM Beacon Award for Most Innovative Client Experience for a DB2 Blockchain solution on the IBM Z mainframe.

McCarthy said Mainline, which says it holds the largest privately owned customer-facing force of IBM engineers and technologists, prides itself on being able to offer the broadest and deepest multi-cloud solution set including IBM and IBM Red Hat. “Customers are demanding a best-of-breed solution set,” he said. “We did 10,000 transactions last year with more than 2,000 customers. They depend on us as a one-stop, end-to-end cloud consultant and solutions provider.”

Joe Mertens, president and CEO of San Antonio-based Sirius Computer Solutions—who has built the onetime IBM-exclusive provider into a $3 billion national integrator powerhouse, the largest IBM partner in the U.S. and No. 21 on the 2020 CRN Solution Provider 500—said he sees the IBM changes as “good news” for partners. “I think IBM has come to the conclusion that they want to concentrate their resources on their largest clients and have the channel focus on the balance, which I think is a positive thing,” he said. “This really gives us additional focus to double down and reinvest in the relationship on a go-forward basis.”

The new IBM focus on the biggest customers draws a clear line between the IBM and the partner-led accounts, said Mertens. “Anytime you are a partner and you have a relationship with an OEM, you want to make sure you don’t have to watch your back. You want to make sure the channel strategy is clear and you know if you engage with them you don’t have to have risk that potentially they could take that transaction direct or through some other alternative route,” he said. “Having clarity to the two different segments should make a real difference in how IBM engages with partners across the country.”

The new strategy also should resolve the differences between the go-to-market models of partner-centric Red Hat and IBM, especially for partners like Sirius, which was a prominent Red Hat partner before the acquisition by IBM.

“The challenge historically was that Red Hat’s go-to-market was different than IBM’s go-to-market, even after IBM bought them,” said Mertens. “With these changes they are trying to align the go-to-market and bring these two things together, which makes a lot of sense. There were certainly challenges prior to that as to what the right route would be, how to go to market and are you partnering with the Red Hat rep or the IBM rep. All that alignment is what I think these changes are designed to help invigorate.”

Besides the new IBM-Red Hat go-to-market model, Mertens expects the spin-off of NewCo “to reduce potential contention” between IBM and partners that have invested in their own managed services capabilities. “Time will tell, [but] on paper it looks very encouraging. We’ll just have to see how it actually happens over time,” he said.

Mertens complimented Krishna as a “technically astute leader” who has IBM sharply focused on hybrid cloud and multi-cloud. “He recognizes that to be successful he has got to rely on the channel and engage with the channel, maybe at a higher level than some of his predecessors,” he said.

With Red Hat OpenShift, IBM is pursuing a write-once, run-on-multiple-clouds strategy, said Mertens. “That is a real advantage,” he said. “It’s not to say that their cloud is better or worse than some other public cloud. There are lots of good solutions out there. What Red Hat gives them is an ability to write once and run anywhere, and that is a big deal.”

As far as the bottom-line investment in partners to drive the hybrid cloud sales charge, Mertens said there is certainly a “verbal commitment,” but it is “too early to tell if there is a fiscal commitment.”

One area that is key to success is for IBM to replicate the IBM Garage services effort in which the company helps fund application modernization proofs of concept in the midmarket with partners like Sirius. Right now, IBM Garage is focused on the largest customers.

“One of the things that I would suggest to IBM is they need to figure out how they fund partners to do those types of proofs of concept for that second segment of customers. … The question is: ‘Is there a way for IBM to help fund those POCs on behalf of the partner?’” said Mertens. That would go a long way toward accelerating the Red Hat OpenShift cloud in the channel, he said.

Mertens said it is still too early to determine ultimately how big an impact Krishna’s new ecosystems model will have, but he is “cautiously optimistic” about the potential for meaningful change. “I am probably more optimistic about IBM’s changes and go-to-market than I have been in many years,” he said.

Mark Wyllie, CEO of Boca Raton, Fla.-based Flagship Solutions Group, one of the early IBM cloud partners that has provided transformative cloud services for both NASCAR and the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons, said he expects the new IBM go-to-market model to help drive double-digit sales growth for his company around cloud, Red Hat and security. “We are all in on IBM,” he said. “IBM has the flat-out best products for hybrid cloud, AI and security.” Flagship, in fact, has a compound annual growth rate of 38 percent since making its bet on IBM’s cloud strategy in 2013.

One area where Flagship is leveraging IBM’s cloud and Watson AI prowess is an engagement with the Professional Fighters League (PFL), an up-and-coming mixed martial arts (MMA) league. That involves putting chips in the gloves of fighters and using high-tech glasses worn by referees to transform the ring battle into a fullfledged biometric experience for fans. The PFL is betting the next-gen SmartCage data and analytics will give it a leg up over rival MMA platforms. “This is the kind of technology leadership that separates IBM from the rest of the pack,” Wyllie said. “The Red Hat OpenShift software and architecture increases our addressable market by an order of magnitude.”

Even with the breakthrough IBM technology, Wyllie said, key to success for partners is execution in the field. “I’m optimistic,” he said. “I think our future is so bright we have to wear shades. Arvind has made the most significant changes at IBM in the last 30 years. If they do this right, it is going to be a huge win for partners, but IBM has to make sure that Arvind’s vision is executed at the street level and that all of the IBMers in the sales trenches are rowing the boat in the same direction as the partners.”

Krishna, for his part, knows that IBM has to make good on the new simplified partner engagement model. “I think it’s a really important step, though, to face up to [the fact] that we can improve dramatically on our channels,” he said. “You need to acknowledge it first. Otherwise, you just keep trying to make incremental innovations.”

Incremental innovation certainly is not the aim of Krishna, who is driving an audacious reinvention of the 110-year-old company to capture the No. 1 position in hybrid cloud and AI. That means rearchitecting the company he loves to make it much easier for partners to do business and succeed with IBM. “What should it lead to?” Krishna asks. “It should lead to a lot more opportunity for our partners to sell and to make money.”